Why Walking is a Window into the Brain: Understanding the Neurology of Gait

- Nick Moss

- Feb 11

- 5 min read

More Than Just Moving Feet

In functional neurology, we operate under a singular truth: it is always about gait.

While most people view walking as a simple mechanical task performed by the legs, the nervous system sees it as a critical survival mechanism. Every step you take is a high-stakes "safety check" performed by the brain. If the brain doesn't perceive the environment or your body's position as safe, it won't allow peak performance—instead, it prioritizes protection over fluid movement.

Movement is a window into the brain. By observing how you walk, we witness the real-time health of your neural hierarchy. This article decodes the complex neurological symphony of gait, helping you understand how your brain, sensory systems, and developmental history influence every stride.

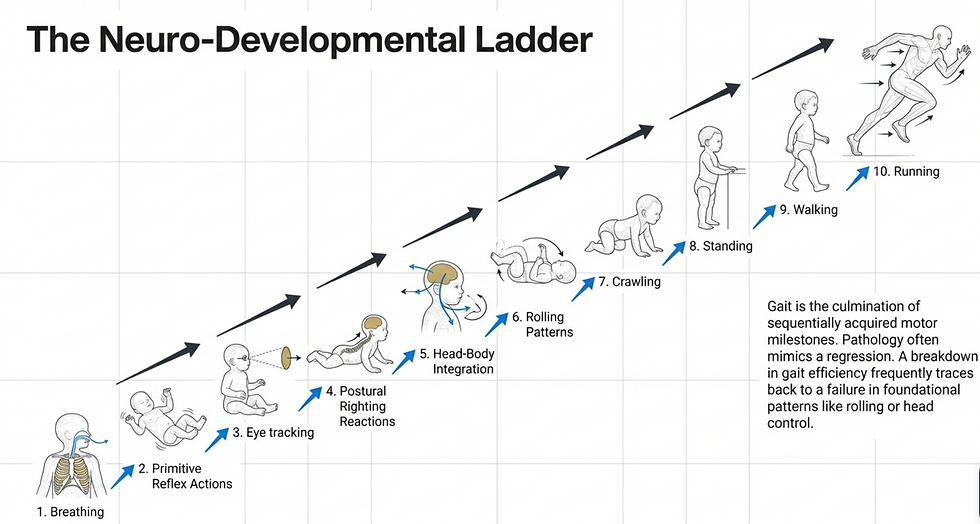

The Developmental Ladder: From First Breath to Final Stride

Human movement isn't accidental—it's the result of a strict neuro-developmental hierarchy. We build movement capacity through thirteen foundational stages. When a stage is skipped or poorly integrated, it creates a "neurological debt" that the adult brain must eventually pay through inefficient movement and compensatory pain.

The 13 Stages:

Breathing – The absolute foundation of the nervous system

Primitive Reflex Actions – Involuntary movements that map initial neural pathways

Eye Tracking – The first stage of sensory-motor integration

Postural Righting Reactions – The brain's ability to maintain an upright head and body

Head-Body Integration – Coordinating skull with spinal movement

Sitting/Falling – Developing core control and protective safety responses

Rolling Patterns – Crucial for rotational mechanics and torso "spiraling" required for mature stride

Rocking – Establishes rhythmic timing needed for locomotion

Crawling – First complex integration of different body zones and cross-body coordination

Standing – Transition to bipedal stability

Walking – Achievement of basic rhythmic locomotion

Running – High-velocity gait requiring advanced neurological coordination

Jumping – Peak of explosive power and motor control

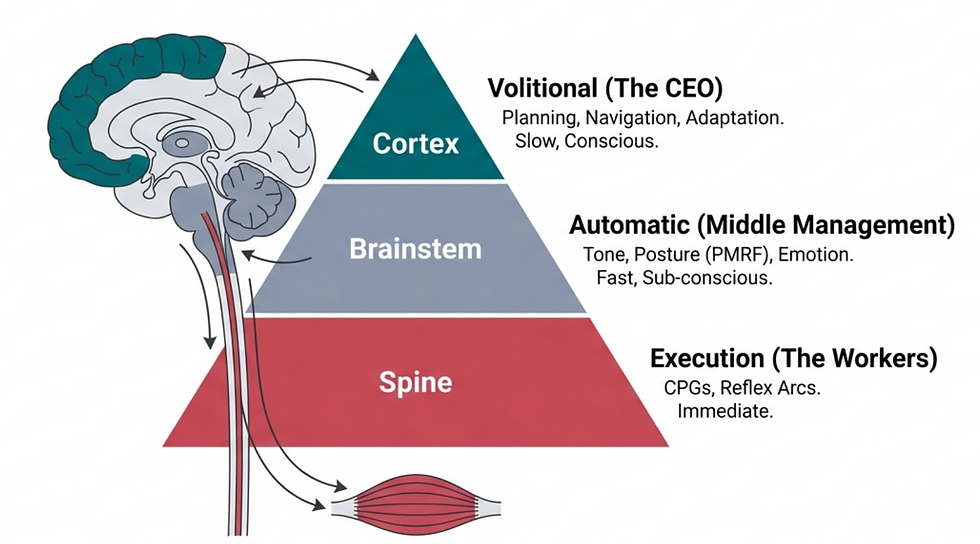

The Brain's Command Chain: Management vs. Workforce

Your movement is governed by a hierarchical command chain that separates conscious intent from automatic execution.

The Cortex (Management): Your conscious brain handles the volitional decision to move—deciding to walk to the kitchen, for example.

The Reflexive Systems (Workforce): Once the decision is made, Management hands the task to the Workforce. This is managed by Central Pattern Generators (CPGs)—specialized neural circuits in the spinal cord and brainstem that handle the automatic, rhythmic patterns of walking.

Two critical hubs in this workforce are the Pedunculopontine Nucleus (PPN) and the Mesencephalic Locomotor Region (MLR). These brainstem centers go beyond simple movement—they integrate visual data and voluntary signals to ensure your walk is responsive.

Remarkably, the PPN is modulated by "imaginary gait." Simply visualizing yourself walking activates these deep brainstem hubs, making mental imagery a potent tool in neurological rehabilitation.

The Sensory Triangle: The Three Pillars of Movement

To move without fear, your brain creates "Sensory Maps"—internal blueprints based on three primary inputs. We call this the Sensory Pyramid:

Visual: What you see and how your eyes track the horizon

Vestibular: Your inner ear balance system that tells the brain where your head is in relation to gravity

Proprioceptive: Physical feedback from joints and muscles. In gait, the feet are the primary feedback mechanics

When these three systems provide conflicting data, a "Sensory Mismatch" occurs. If your eyes see movement but your inner ear doesn't feel it, or if your feet feel unstable, the brain perceives a threat. It immediately defaults to a threat response, resulting in gait that is stiff, guarded, and prone to fatigue.

When the "Baby Brain" Stays On: Primitive Reflexes and Your Gait

Primitive reflexes are involuntary survival responses essential for infants. Ideally, these should "integrate" (become tucked away) as the brain matures. If they remain active due to stress or injury, they act as neurological "glitches" that disrupt adult gait.

Reflex Name | Affected Gait Phase | Specific Muscle Action | Visual Sign |

ATNR | Swing phase | Locks arm extension; hinders opposite leg swing | Uneven stride; shortened step on "face-side" |

STNR | Stance to swing transition | Neck flexion locks knees in extension; neck extension delays knee flexion | "Bunny-hop" or very stiff-legged gait |

TLR | Early stance (loading) | Head-back causes hip/knee hyperextension; head-forward causes crouched posture | Toe-walking (head back) or hunched, flexed posture |

Moro (Startle) | Mid-swing interruption | Sudden co-contraction of hip flexors and knee extensors | Abrupt freeze or "reset" of rhythm mid-stride |

Fear-Paralysis | Any weight-shift | Amygdala activation causing instant gait arrest | Whole-body "freeze" when threat or pain perceived |

Tendon-Guard | Loading to mid-stance | Sudden inhibition of overloaded extensors (e.g., calf) | Knee/ankle buckling, hip hitching, or unstable stance |

Spinal Galant | Weight-shift/Pelvic phase | Exaggerated lateral trunk flexion and pelvic hiking | Waddling gait; uneven hip drop during weight transfer |

Babinski | Initial contact | Abnormal toe dorsiflexion (toes pull up/fan out) at strike | High-arched foot landing; lack of smooth heel-to-toe roll |

The Three Zones of Movement Neurology

In clinical practice, we decode gait by analyzing three distinct neurological zones:

Zone 1: The Brain and Sensory SystemsTop-down control involving the Cerebellum and the PMRF (Pontomedullary Reticular Formation). The PMRF coordinates your "Ipsilateral Gait" (same-side posture). It operates on a T6 neurological split: it drives flexion above the T6 vertebrae (causing internal rotation of the shoulder) and extension below T6 (causing external rotation of the hip). This explains why a slumped shoulder and a turned-out foot often appear on the same side of the body.

Zone 2: The CoreInvolves the CPGs and integration of the pelvis, ribcage, and cranium.

Zone 3: The FeetThe primary mechanoreceptive feedback system—the "tires" of the vehicle.\

Pathophysiology: How Injury Disrupts the Map

Gait dysfunction usually results from a breakdown in communication, categorized as either Top-Down or Bottom-Up disruptions.

Top-Down (e.g., Concussion)

A concussion disorganises the brainstem and cerebellum, leading to "Sensory Disintegration." This trauma often "disinhibits" primitive reflexes that were previously integrated, causing the adult brain to revert to "baby brain" movement patterns. The result is distorted feedback loops where the brain can no longer accurately map the body in space.

Bottom-Up (e.g., Old Ankle Sprain)

When a runner severely rolls an ankle (inversion injury), the brain's priority is protection. To prevent another roll, the brain automatically inhibits muscles along the lateral chain and the core. It creates a "Neuro tag"—a stored memory that perceives every step as a threat via nociceptive (pain-sensing) pathways. This effectively "handcuffs" your core, leading to hip and back issues long after the ankle tissue has healed.

Clinical Insights: What We Look For

To assess the health of your movement neurology, we utilize specific diagnostic markers:

1. Marching Patterns We look for "Cross Lateral" movement (opposite arm and leg moving together) versus "Homolateral" marching (same side arm and leg), which indicates a failure in neural integration.

2. Sensory Loading We observe how your gait responds to extra stimuli—counting, answering questions, or listening to specific sounds. If your walk falls apart under these conditions, it proves your gait isn't automatic—the Management (Cortex) is still doing the Workforce's job.

3. Symmetry and Speed We look for stalling, loss of speed, or lack of coordination between left and right sides of the body.

Conclusion: The Path to Integration

True rehabilitation requires more than stretching a tight muscle or strengthening a weak leg—it requires rehabbing the neurology itself. By identifying which zone is failing—whether it's the Sensory Map in Zone 1, the Core Patterns in Zone 2, or the Mechanics of Zone 3—we can apply targeted interventions.

When the brain feels safe and the sensory map is clear, the nervous system stops "guarding," primitive reflexes settle, and healthy, efficient gait returns.

Movement is a window into your brain. Our goal is to ensure that what we see through that window is a picture of balance, safety, and integrated health.

Are you a practitioner who wants to learn the details behind our comprehensive Functional Neurological Approach? If so book in for a discovery call here to see if you are a fit for the depth that we offer in our approach.

Comments